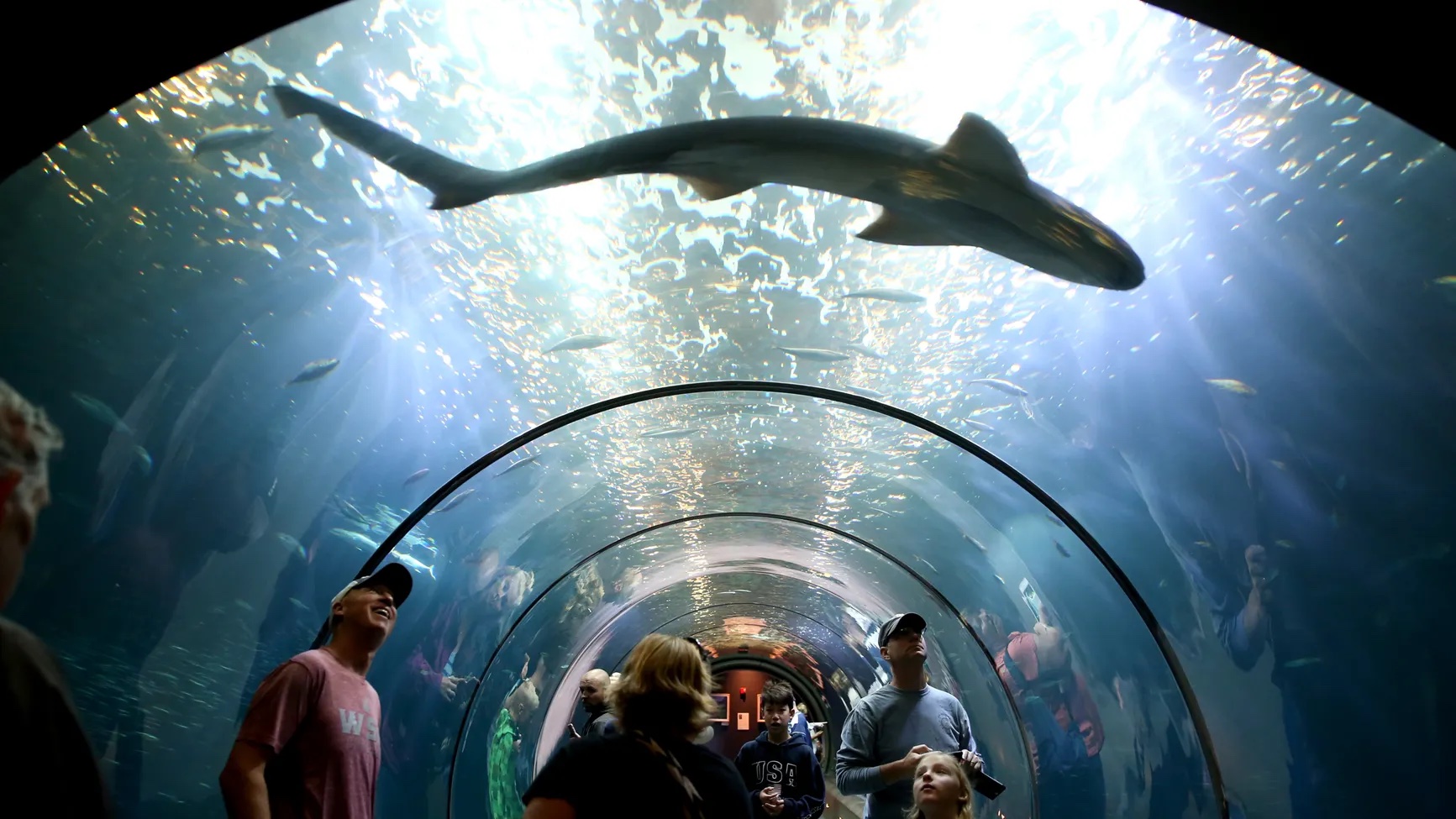

What comes to mind when you hear the word shark? Many envision large, dangerous predators to be avoided at all costs. However, some individuals venture out in search of sharks, endeavoring to better understand the crucial role they play in marine ecosystems.

The Oregon Coast Aquarium (OCAq) partners with Oregon State University’s Big Fish Lab (BFL) to study sharks, focusing on their movements, behaviors and population dynamics.

Taylor Chapple, an associate professor with OSU’s Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Sciences, was the driving force behind development of the Big Fish Lab about six years ago.

“Historically, there’s been very little shark research done in the Pacific Northwest,” said Chapple, “so we’re doing a couple of things. One is just getting the fundamental baseline information about where they’re at and where they’re going. But more broadly, what we’re interested in is the role that these sharks play in our marine ecosystems, whether that’s a role as a predator or that’s a role as a prey as well.”

As he was getting his research underway at the Big Fish Lab, located at the OSU Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport, Chapple reached out to Jim Burke, OCAq’s Director of Animal Care.

One of the primary species being studied in this project is the broadnose sevengill shark. “I didn’t have a clue about sevengills, but I knew that the aquarium had experience with them,” Chapple said. “So I contacted Jim Burke, and he and his team have been really essential for the projects that we have going.”

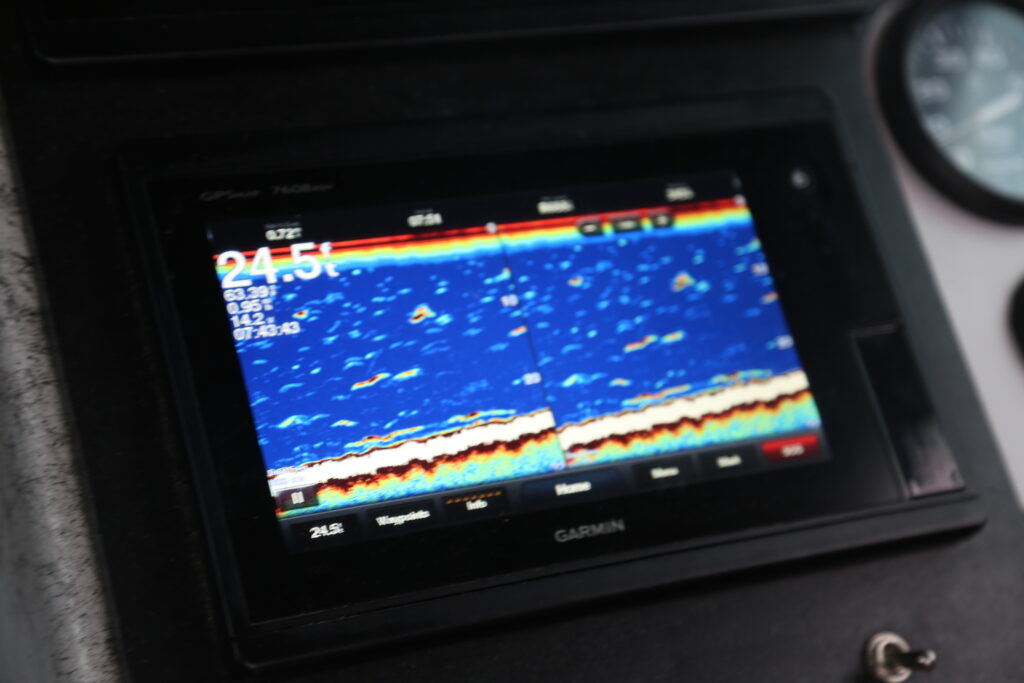

Recently, OCAq’s research vessel, the Gracie Lynn, voyaged to Willapa Bay, which is right inside the Long Beach Peninsula on the Washington coast. The mission was to tag broadnose sevengills so they can be tracked, and to collect samples to learn more about each individual shark.

Aboard the boat were Burke and other OCAq personnel, as well as members of the Big Fish Lab team.

“I have over 20 years of working in Willapa Bay and understanding where the sharks hang out,” Burke said.

Once on site, they set a line with a baited hook, attached to a couple of high-visibility buoys. They keep their eyes on the floats, waiting for a telltale jerk. When a buoy shows movement, they haul the line up and guide the shark into a stretcher placed alongside the vessel. The stretcher is then brought on board and placed in a large tank of saltwater, pumped in directly from the bay.

The goal is to have minimal impact on the shark while samples are collected and tagging is done. To help reduce stress, the team covers the shark’s eyes and adjusts the water parameters.

“We increase the oxygen percentage in the water to 120 to 125 percent,” Burke said. “That helps them calm down and be more docile.”

The calmer an animal is the less energy it expends, and the quicker the team can get their work done and return it to the bay.

Doug Batson, OCAq’s Dive Safety Officer, is part of the research team, and he described working with the sharks aboard the boat as “a little bit like being on a NASCAR pit crew. Once you get the animal on board, it’s like everybody’s got a job and you’re just trying to kind of dance around each other, get your samples, get your tag in, all those things.” Typically, the shark is on board for just 6 or 7 minutes before being released.

Chapple said the retrieved samples allow them to see what a shark has been eating. This provides data on their diets, including preferred prey and general availability. “We can actually figure out what they’ve been eating over a longer time period, from a few weeks to a few months up to a year.”

The acoustic tag implanted on the shark allows researchers to track movement and identify patterns over time. It was thought the sharks would summer in northern waters and then migrate down to California for the winter. However, this past year, some sharks were recorded spending the winter on Stonewall Bank, which is about 15 miles offshore from Newport.

In terms of how this work coincides with OCAq’s mission, Burke said “We want to contribute to new and influential biological science and research, especially as it pertains to our exhibits and animals. We aim to educate people about marine life, ocean current events, and conservation, and joining these research efforts supports that goal.”

As far as OCAq’s collaboration with Big Fish Lab, Burke added, “I feel it’s really fortunate for Oregon to have Dr. Chapple and the Big Fish Lab here on the coast. They’re great neighbors to work with. I think between our efforts and theirs, we can really make some progress in better understanding shark behavior.”

More information about research being done by the Big Fish Lab can be found here.