They’re called nurdles, and while you may never notice them while walking along the ocean beaches, you could literally be stepping on hundreds of them.

A nurdle is a small plastic pellet that serves as the raw material for manufacturing plastic products. They are often transported in bulk and can easily be spilled or leaked into the environment during production or transport. Once in the environment, particularly in waterways and oceans, nurdles can be mistaken for food by marine life and can also absorb toxic pollutants, causing harm to ecosystems and potentially entering the human food chain.

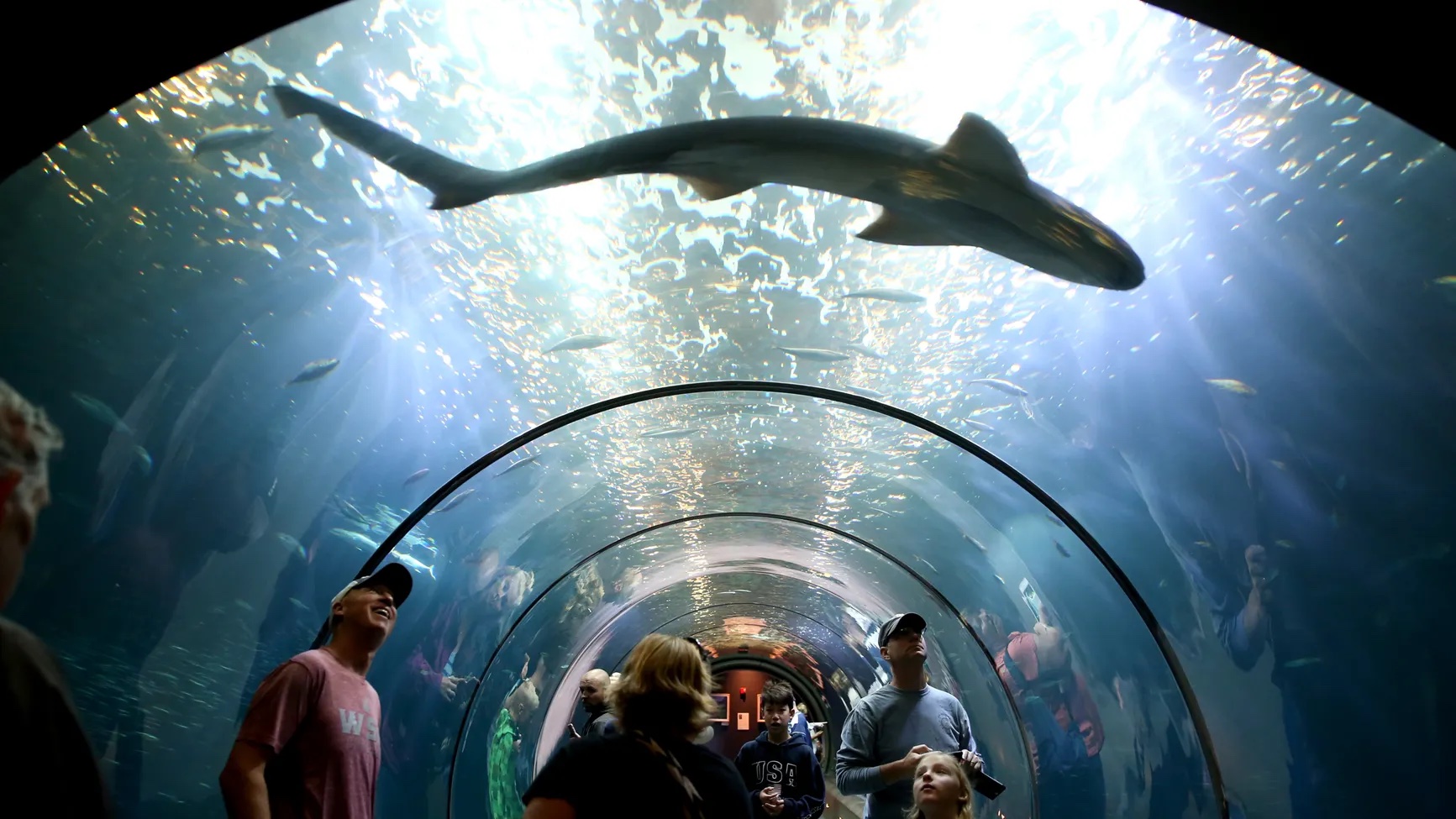

The Oregon Coast Aquarium (OCAq) is helping raise awareness about this issue through a new program called the Nurdle Patrol, organized by Shelby Smith, OCAq’s Conservation Engagement Manager. Partnering with Oregon State Parks, she helps raise awareness each week by operating an information table on Sundays at the Depoe Bay Whale Watching Center, followed by beach excursions at South Beach State Park (Mondays from 10 a.m. to noon) and Beverly Beach State Park (Tuesdays from 10 a.m. to noon). Anyone is welcome to attend one of these free events.

Because of the currents and tides, Beverly Beach, located just north of Newport, has one of the highest concentrations of nurdles anywhere in the U.S. during the wintertime.

So why are these very small, sometimes nearly invisible pieces of plastic a problem?

“The smaller the plastic, the bigger the impact it has on the environment because these are what actually get eaten,” said Shelby. “For some animals, it’s no big deal, but if you’re a small animal and your digestive tract is not that large, it will sit in your stomach. Stomach acids are not strong enough to break down these types of polymers and plastics, so even though that animal has a full stomach, it will die of starvation.”

The toxins absorbed by nurdles can also move up the food chain as larger animals consume smaller ones that have eaten the pellets. This can have significant impacts on marine ecosystems and potentially affect human health through seafood consumption.

And how do these nurdles end up on the beach in the first place?

“There’s two main ways that they get into the waterways,” Shelby said. At the factories, they can fall off the production line onto the floor and eventually can get washed down drains and out to sea. They can also get into the environment because of a spill during the shipping process, either from a cargo transport ship or a railroad car.

As a single example, in 2021 a large cargo ship capsized off the coast of Sri Lanka, dumping around 9,000 pounds of nurdles into the ocean. “A nurdle weighs nothing on its own,” Shelby said, “so for 9,000 pounds to have been lost, that’s literally millions of nurdles.” She added that in 2020, a spill occurred in the New Orleans port, and in 10 minutes, using a massive net, about 500,000 nurdles were collected.

Why is OCAq involved in raising awareness of this problem?

Shelby launched the Nurdle Patrol program earlier this year, curious to see what the response might be, “and it just exploded,” she said. “We’re really hoping that in the future we can implement this on a larger scale.”

A recent Nurdle Patrol excursion at Beverly Beach drew more than two dozen participants of all ages, and there was a lot of excitement as people poked around among large piles of driftwood looking for these little plastic lumps. Each person earned a commemorative Nurdle Patrol sticker as a reward.

“Our mission is to create unique and engaging experiences that connect people to the Oregon Coast and inspire conservation,” said Shelby, “and part of that involves going out and being hands-on in nature, and seeing it for yourself.”

Nurdle Patrol is part of OCAq’s Community Education Initiatives. Click here for more information about Nurdle Patrol outings or other programs, or contact Shelby at communityscience@aquarium.org.